30 Sep Anatomy Set in Stone, 22 Mosaics of Eustachi’s Anatomical Engravings.

What I’m Building

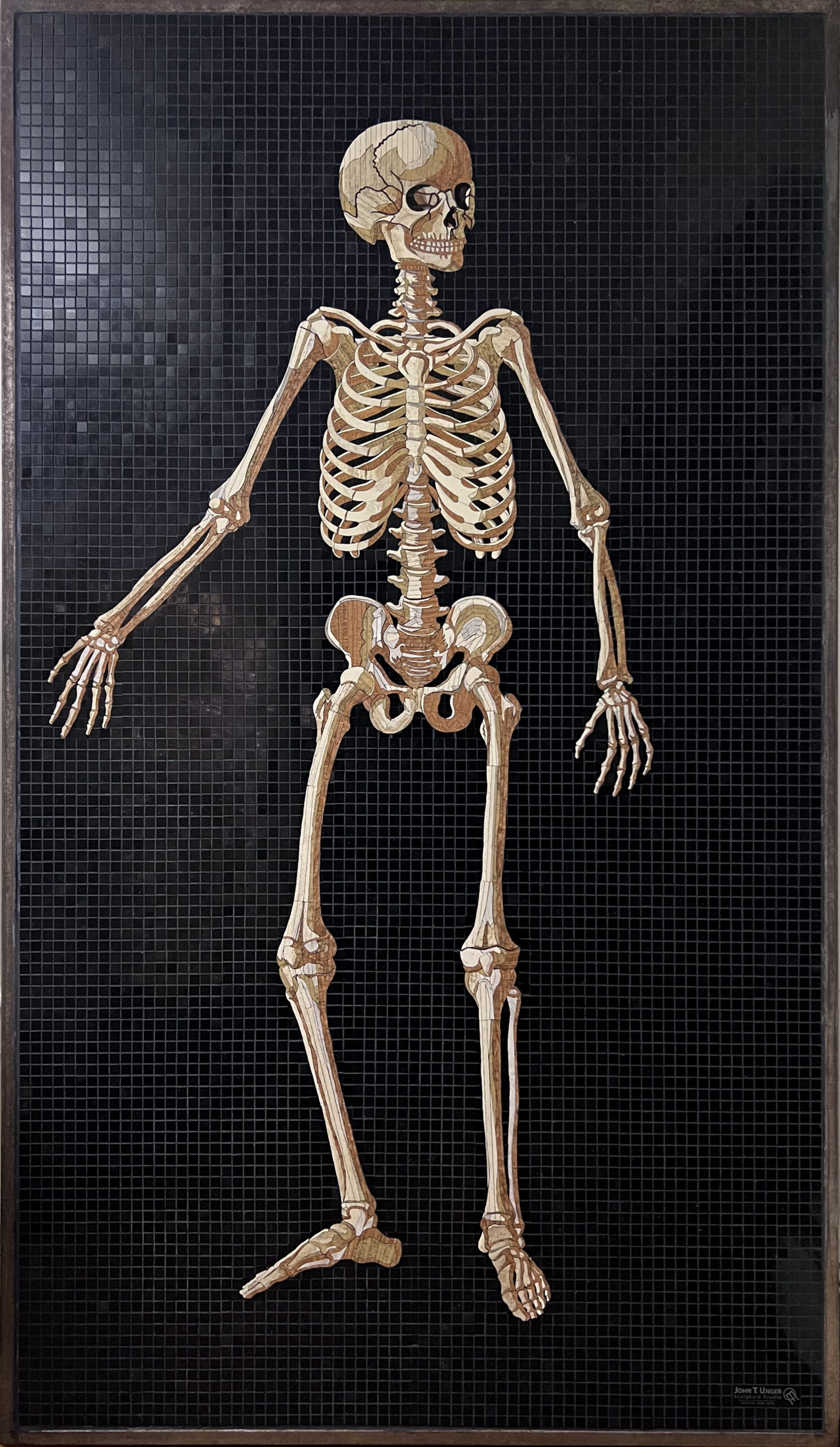

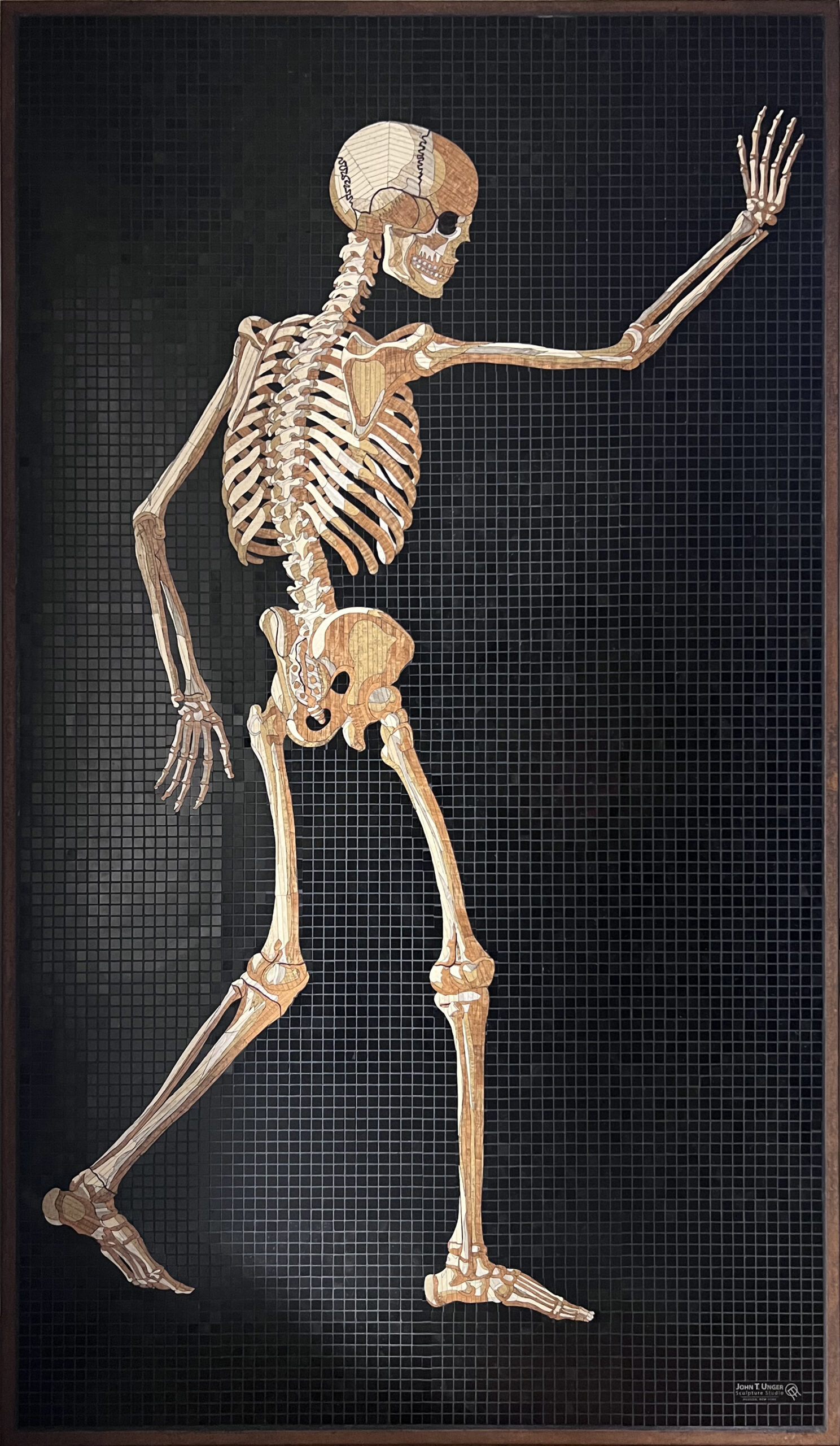

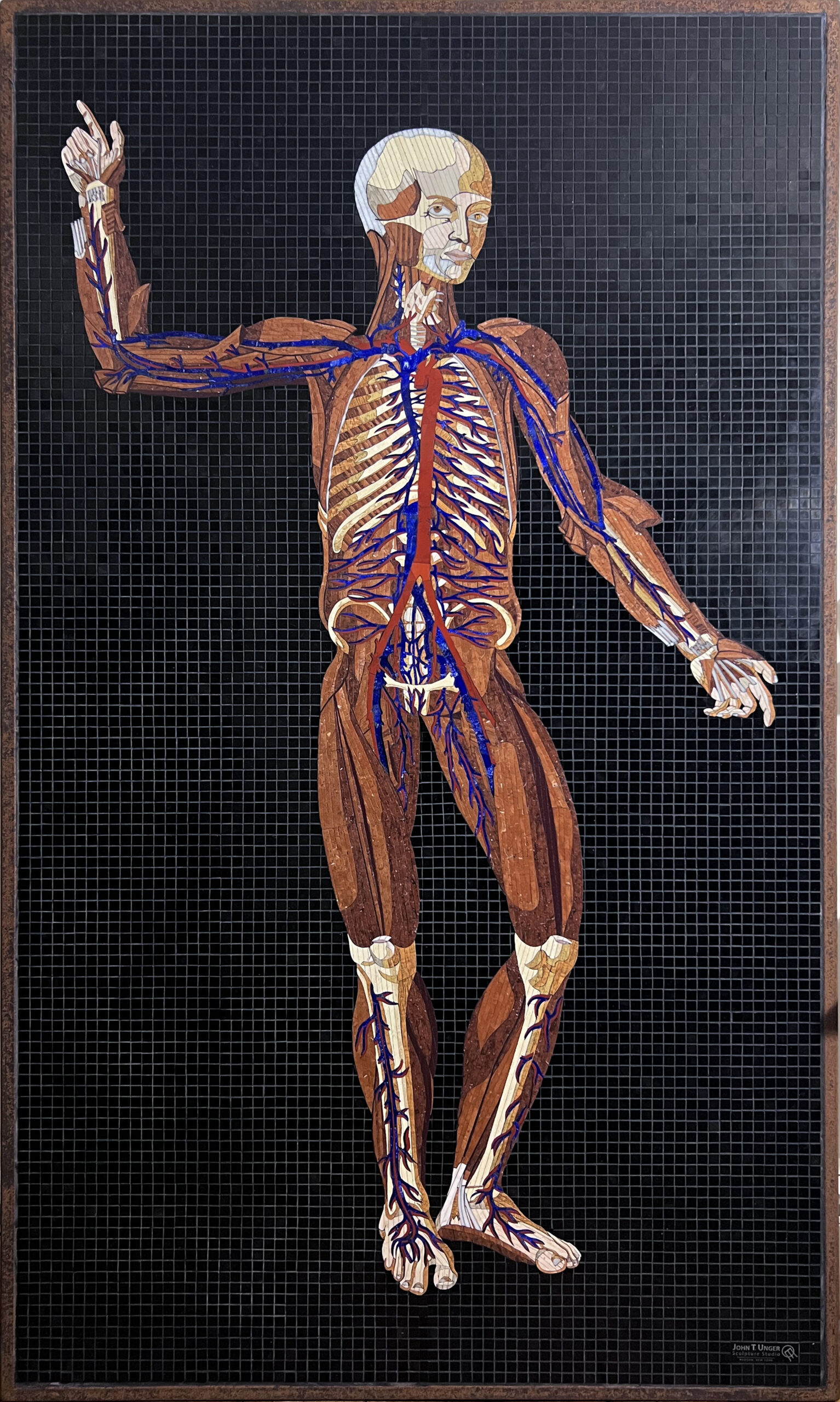

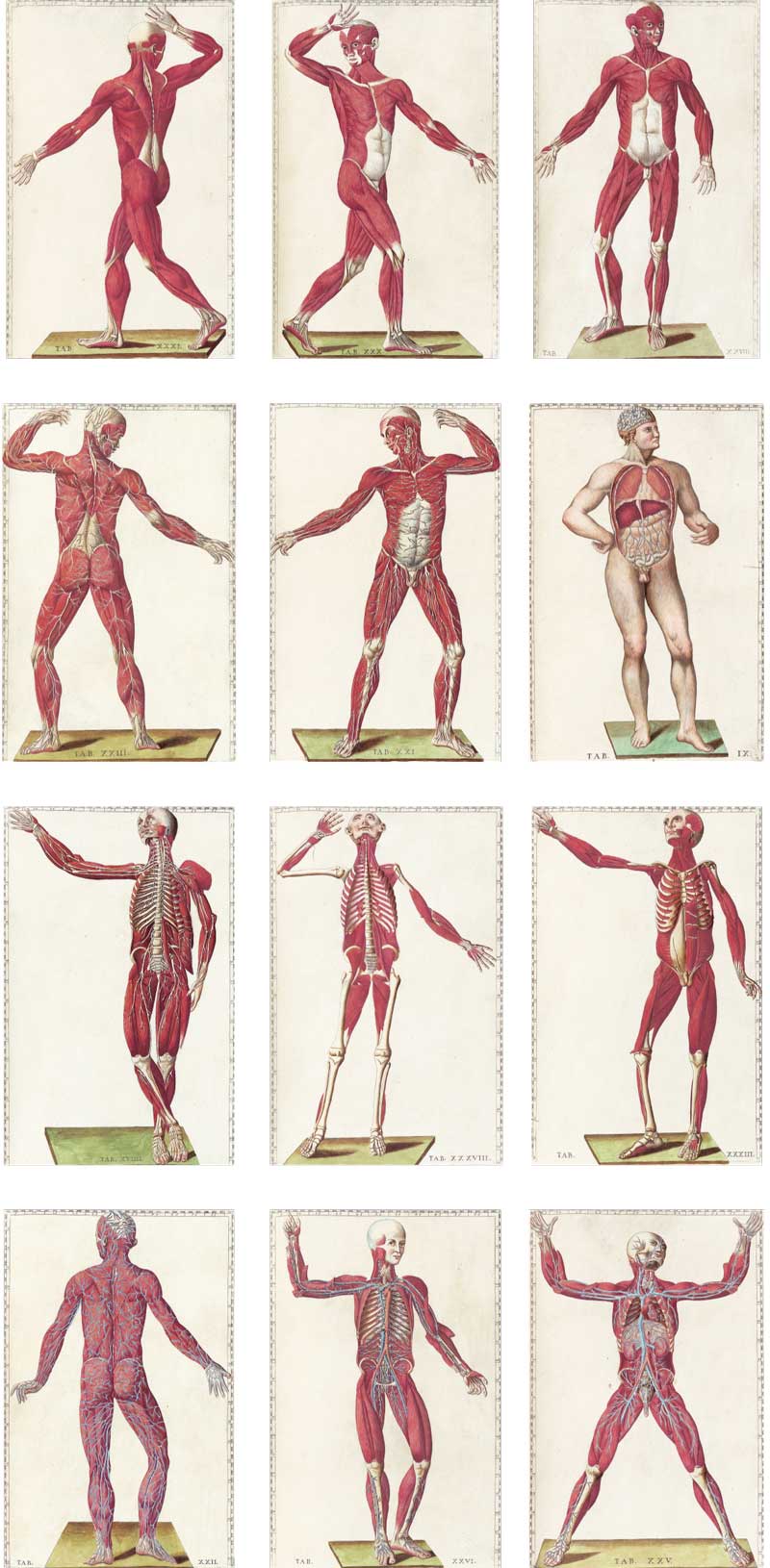

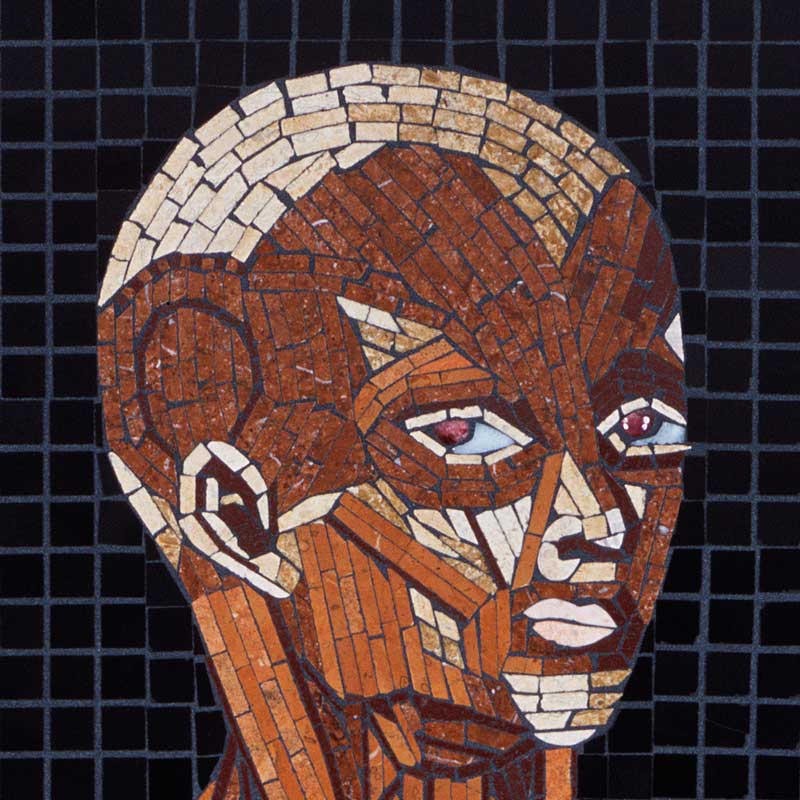

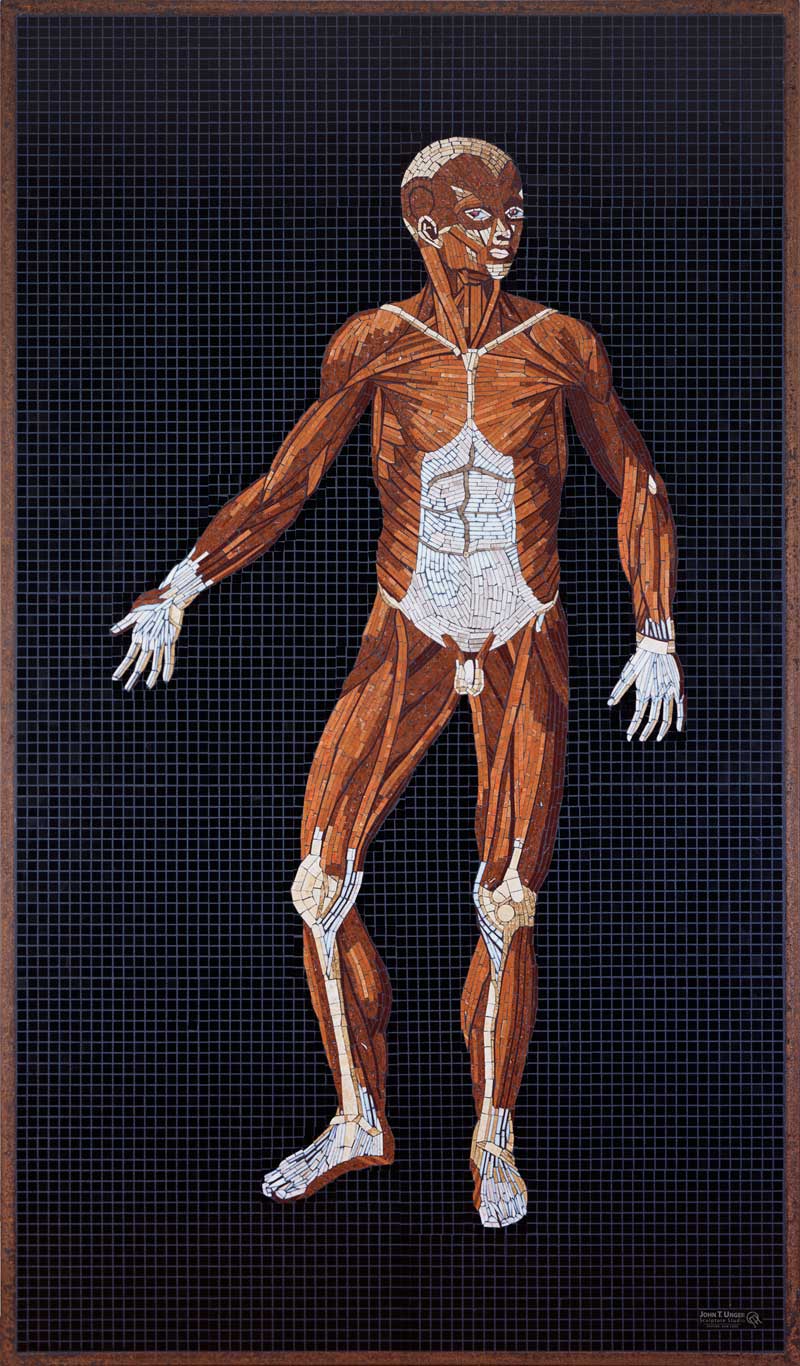

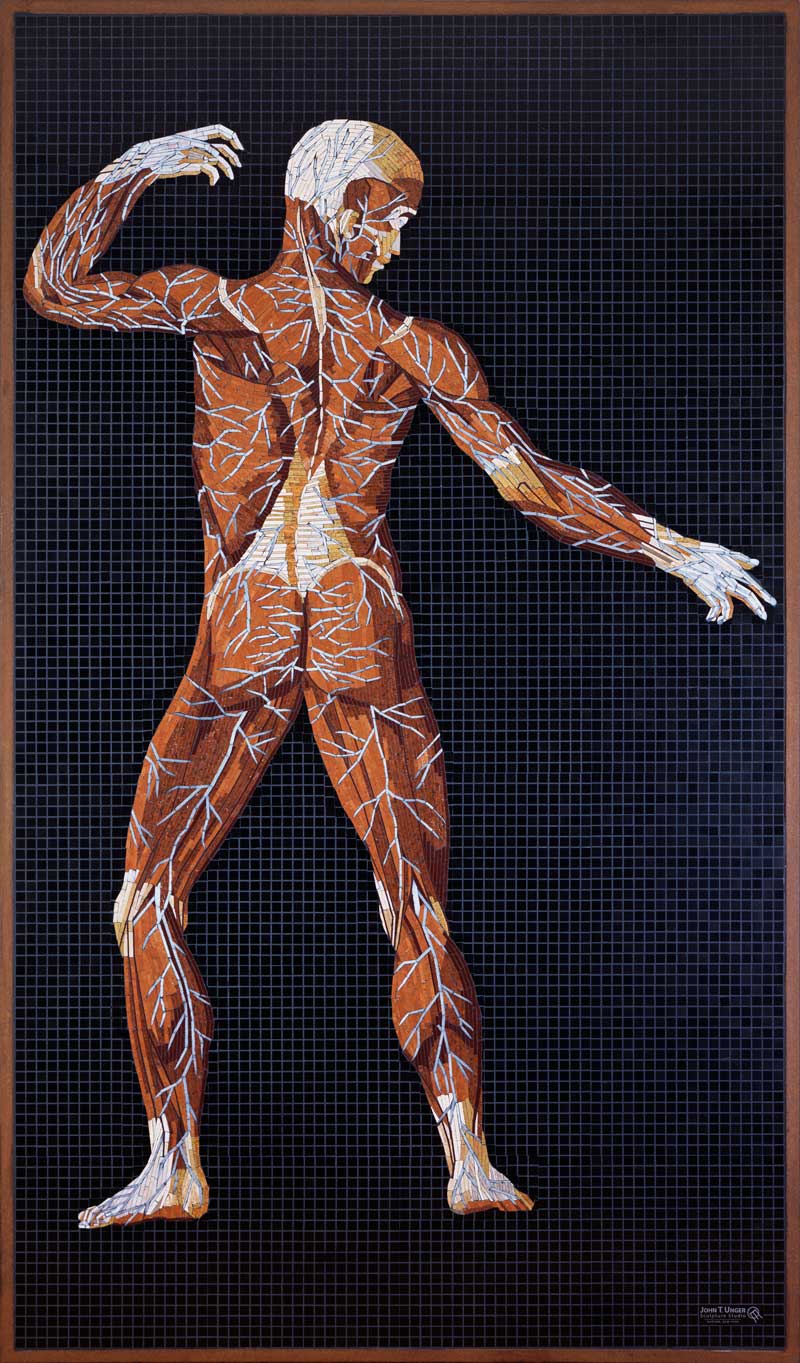

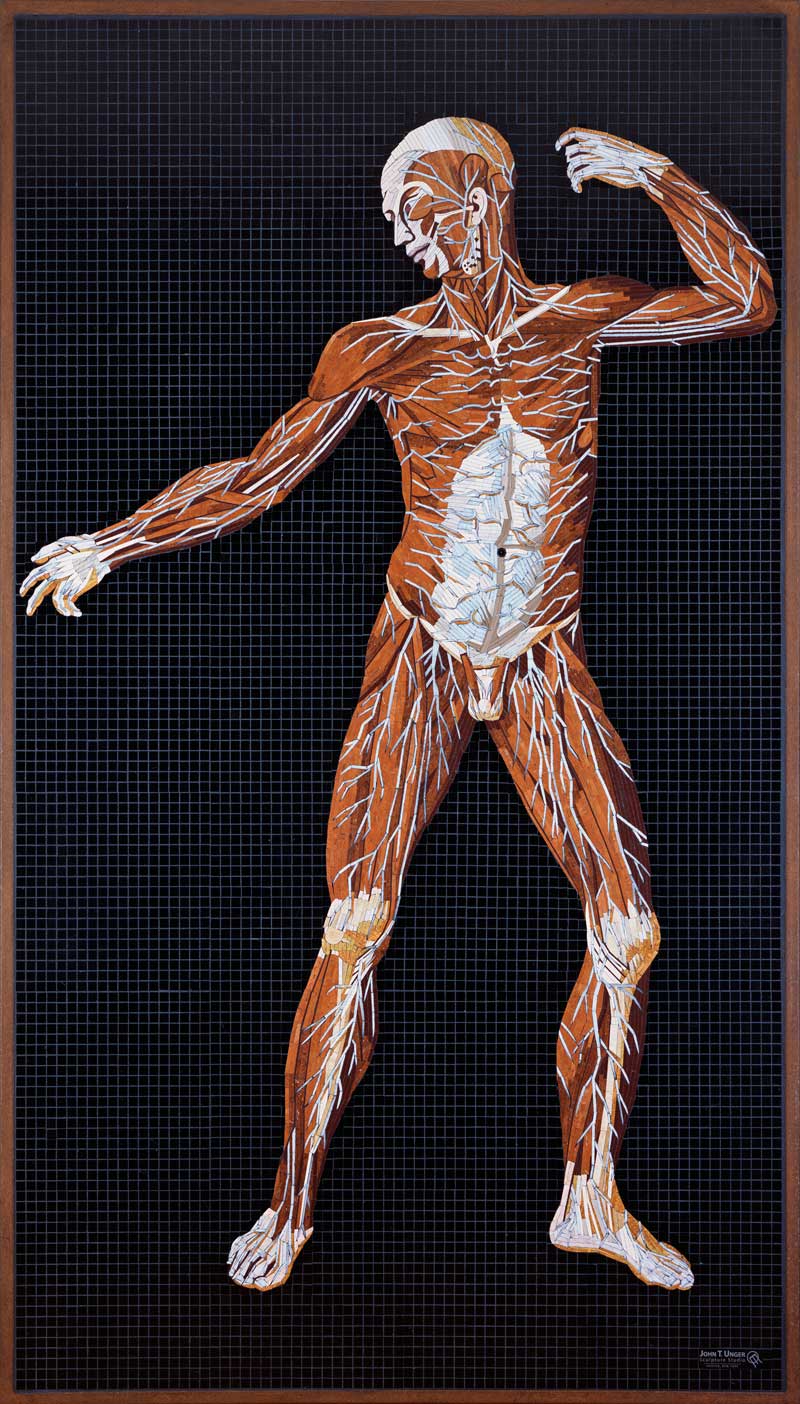

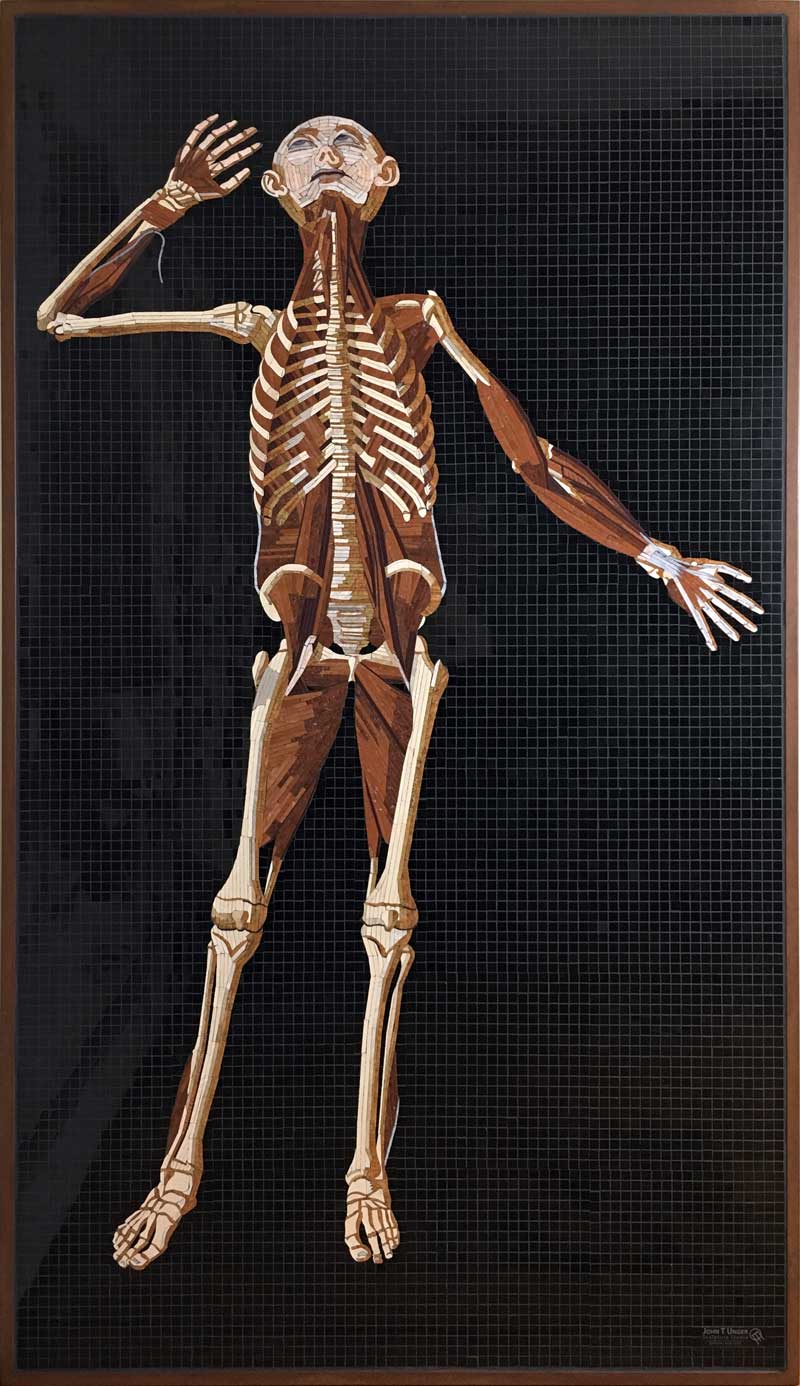

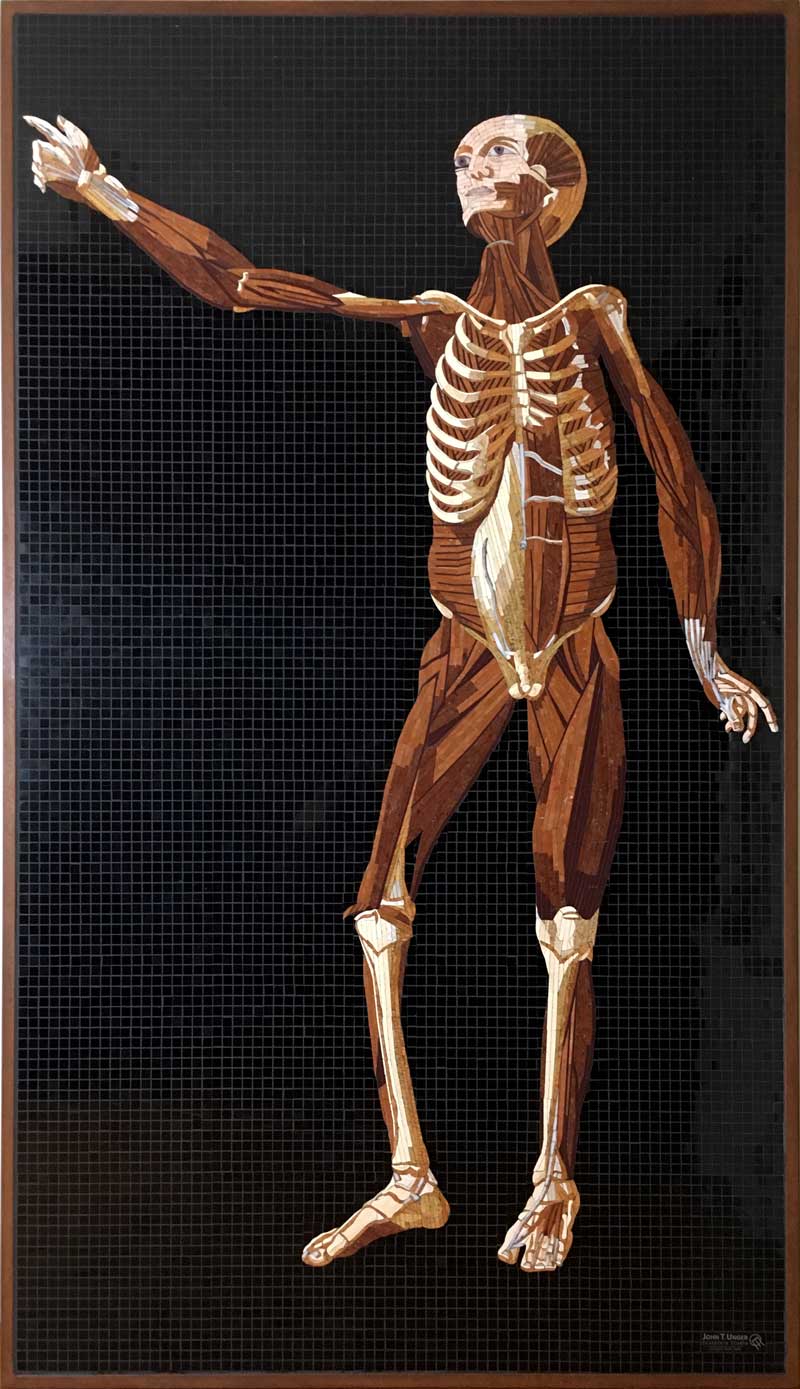

Anatomy Set in Stone is a series of 22 life size mosaics that replicate Bartolomeo Eustachi’s 16th century anatomical engravings in marble, stone and precious gems. The mosaics are composed mainly of marble, travertine, onyx, limestone, blue and pink quartz. The eyes are black garnet and star ruby, sapphire or tiger eye. The veins and arteries are lapis lazuli and red jasper. Thirteen mosaics are now finished with the fourteenth underway, bringing the project to a bit over 50% complete.

As each mosaic is finished, it is added to the bottom of this page. Scroll down to see large photos of all the finished work.

Each mosaic is seven feet high by four feet wide (86.25″ x 50.25″ including the steel frame) and presents the figures at life size— viewers can stand before them and see anatomy as though looking in a mirror.

I plan to tour the finished mosaics as a museum exhibit with the original drawings displayed next to the mosaics for comparison. The original mosaics are not for sale— they will be kept together as a set. Currently, the finished mosaics can be seen at my Hudson, NY studio Friday, Saturday and Sunday from Noon to 7PM or by appointment.

Anatomy Set In Stone has been featured in Smithsonian Magazine, The Washington Post, Atlas Obscura, Boing Boing, Laughing Squid and Kottke.org.

Carrie Haddad Gallery in Hudson, NY debuted the Anatomy Mosaics, June 12th through July 28, 2019

A 56 page full color book documents the 13 Anatomy Set in Stone mosaics completed so far as well as the 9 engravings remaining. The book reproduces the mosaics side by side with the original etchings of Bartolomeo Eustachi’s Tabulae Anatomicae at the same scale. Prints of the mosaics are 13.5 inches tall, providing a much higher level of detail than images shared online. The wire binding lets the pages lie flat inviting easy comparison. If you’ve been following the project over the last 8 years, this is a great chance to see the mosaics at a larger scale all in one place.

When we speak of truth, or scientific reason, we often use the phrase “set in stone.”

There are moments in the history of science and medicine deserving of monuments— great accomplishments that changed the world, our perception of it, or both. I have undertaken a project to literally set in stone one such discovery.

Of course, it is the nature of science to examine and question both the world and itself, and so knowledge is added and amended over time. Were stone the medium of recording scientific discovery, newly discovered facts would be chiseled over the old and at moments of great revelation, we would have to create new tablets altogether to correct for the errors of previous beliefs.

The U.S. National Library of Medicine was kind enough to provide high resolution scans of their 1873 edition of Bartholomeo Eustachi’s Tabulae anatomicae so that I could print the engravings large enough to serve as guides for the mosaics.

Of the forty-seven plates Eustachi produced with the help of Pier Matteo Pini, I first chose the following twelve to render in mosaic.

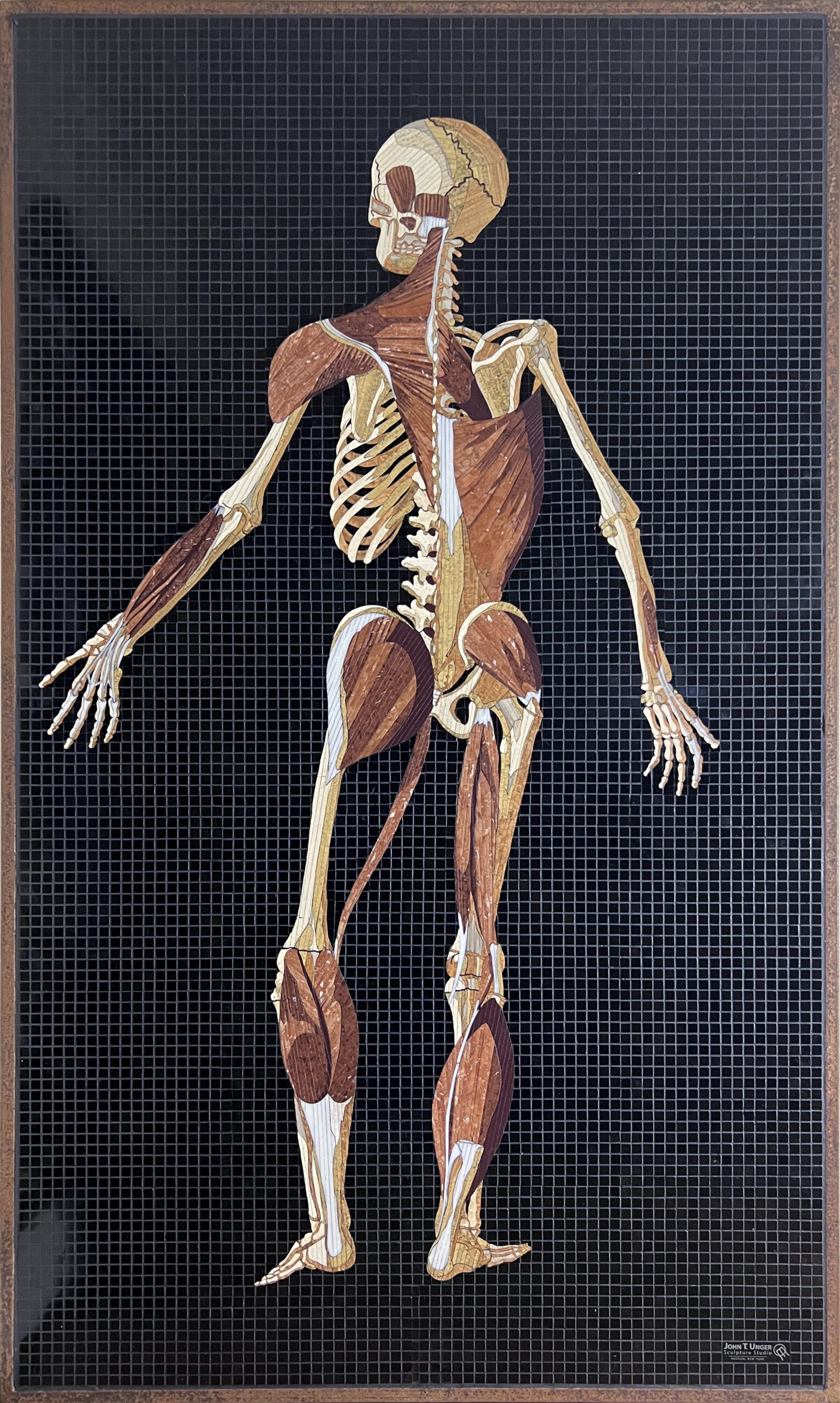

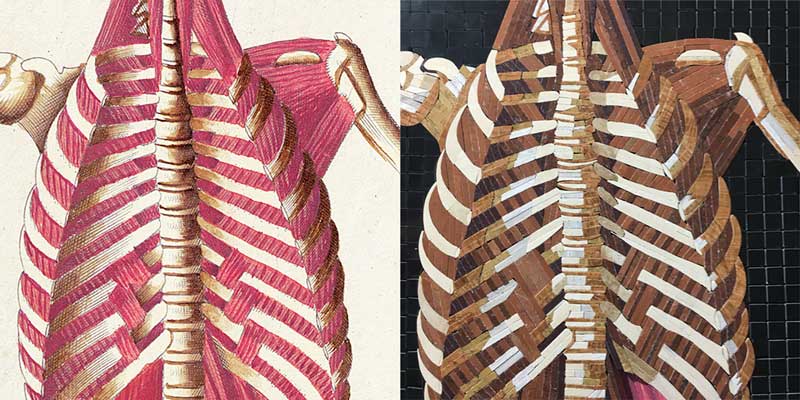

Originally I didn’t plan to do the the two plates that detail the skeletal structure because I wasn’t confident that I could do them justice in stone— I felt they might be too flat. But I’ve added to my skill and my palette as I’ve worked. The mosaic of Table 38 has a lot of exposed bone which I was able to shade beautifully with stone. Look at how much depth, color, lighting and shadow is present in the rib cage below… it’s almost 3D and looks more like a painting than a mosaic!

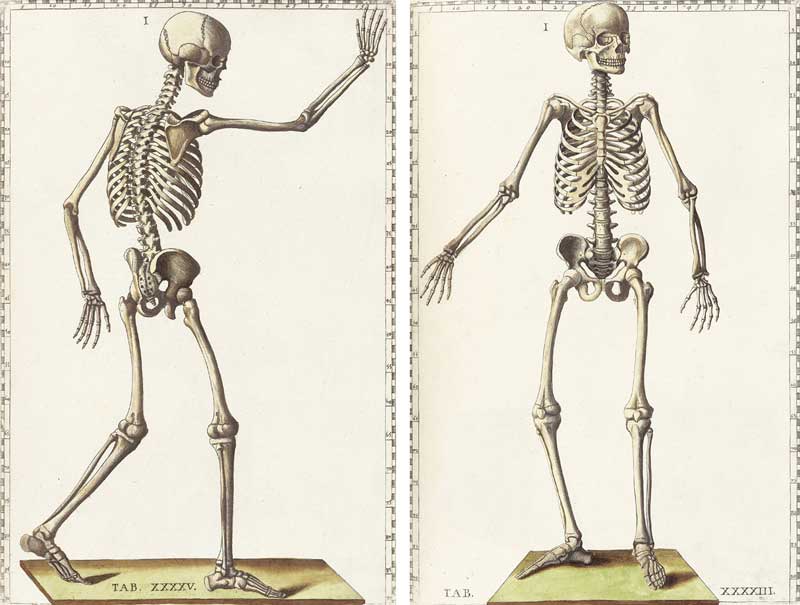

Side by side comparison of the mosaic and the original etching of Table 38 of Eustachi’s Tabulae anatomicae.

As a result, I decided to add two more mosaics to the project, bringing it to a total of 14 pieces.

Later, I discovered that there were eight more full size figures I had previously been unaware of. The poses in those were so gorgeous that I really couldn’t leave them out of the project!

It took almost a year and a half to get photos of them as the U.S. National Library of Medicine was mostly closed during the pandemic but I have them now. I’ll be alternating between the highly detailed images of the circulatory system and these new images from here on out— The lapis lazuli and red jasper I’m using for the veins and arteries is gorgeous but cuts very slowly. In between those I need to give myself a break and tackle a simper image.

Detail of Marble Mosaic of Table 26 with lapis and jasper veins and arteries. Tiger eye was used for the iris of the eyes.

The genesis of this project is so simple it almost feels ludicrous—

I simply realized that minerals and stone dug from the body of the Earth come in exactly the right colors to portray the interior of the human body.

In 2005, I did a small anatomical mosaic as a commission for a massage therapist. Budgetary constraints limited that piece to a partial torso, but I have been haunted ever since by the desire the render the full illustrations at life size. More than anything, I wondered whether it would even be possible to get the level of detail needed to render both the drawing and the underlying anatomy accurately?

Few people would feel compelled by such a thought to cut over 5 miles of stone by hand, spending several years and over a hundred thousand dollars to fashion it into 616 square feet of detailed mosaic. But one of my core practices as an artist is to match the material to the meaning in my work. A good example would be my La Siren Mosaics (including a recent commission for the American Museum of Natural History). These use bottle caps for the tail of the mermaid suggesting both scales and the sequins used to portray La Siren in Haitian flags. The challenges of working in new ways with different materials is often the largest part of my inspiration.

Another motivation for this project was the intersection of art and science in a time when I feel we need more of both. Since early childhood I’ve been fascinated with art, natural history, geology and minerals, scientific inquiry and antiquarian books. This project allows me to dovetail all my intellectual interests and explore their overlap.

Perhaps this project is also a bit of reactionary anachronism. Much of the maker scene is about using CAD, CNC and 3D printing to render objects in unlimited number… digital is appealing because you can draw something once and endlessly iterate it. Much of the fine art scene is conceptual art or art designed by the artist but produced by assistants and specialists. Attention spans are short and artists are rewarded for working quickly to hop a trend (or start one), generating as much content as possible to compete with the endless spectacle of click-bait entertainment.

I feel drawn to the long con… I don’t want to compete for 15 seconds of fame when the spot light resembles a strobe light. I want to take my time to make something that will last. A magnum opus, a serious body of work.

As an artist, I like to get my hands dirty— I like to work directly with natural materials, using my hands to shape each piece of the whole towards creating a one-of-a kind work that will last for centuries. I feel that this project is about as old-school and analog as you can get. Of course I use power tools, but they’re guided by my hands. I’m taking stone and minerals mined from the earth, cutting them to size on a saw, hand-shaping them with tile nippers, smoothing them on a lapidary wheel, all to reproduce drawings from the 16th Century. These drawings were drawn by hand at the direction of a surgeon as he dissected an actual corpse, then etched into plates and printed in books made one at a time on a hand operated press. The color in each book was hand painted. Every stage of both the books and the mosaics required great attention to detail and work by hand.

Detail of Marble Mosaic of Table 21

Who is Bartolomeo Eustachi and why did I select his drawings to work from?

I chose Eustachi’s drawings to work from because of their beauty and also because being in color they were easier to interpret than Vesalius’ black and white illustrations. The choice is also an act of reverence and preservation of knowledge from antiquity— the fact these drawings are still accurate and relevant after 465 years feels like they deserve to be immortalized— and since mosaics can last thousands of years, that seems like a good way to honor and preserve them.

Bartolomeo Eustachi, one of the first modern anatomists, is also considered the first comparative anatomist, as he was the first to use examples from the animal realm for comparison and clarity. Eustachi was a contemporary of Vesalius, and they share the credit of having created the science of human anatomy. In 1552 (nine years after Vesalius published his Fabrica) Eustachi completed a series of anatomical illustrations so accurate that had they been published in his lifetime, a modern understanding of anatomy might have come to pass two centuries before it was attained.

Sadly, all but eight of the drawings were lost for 162 years following his death. The engravings were re-discovered in the early eighteenth century and purchased by Pope Clement XI, who gave them to his physician Giovanni Maria Lancisi. Lancisi, a successor to Eustachi in the chair of anatomy at the Sapienza, published the plates in 1714 as Tabulae anatomicae Bartholomaei Eustachi quas a tenebris tandem vindicatas (Anatomical Illustrations of Bartholomeo Eustachi Rescued from Obscurity).

The experts all said it was impossible—

In previous stone mosaic projects, I’d only worked with 5/8″ square mosaic tiles, cutting them as needed with tile nippers. For this project, I really wanted longer, thinner strips of stone to better emulate strands of muscle, tendons, cartilage or fascia. Initially I had hoped to be able to buy the stone pre-cut into strips, but that was only available in color blends. Having it done custom would have been too expensive and too long a wait. When I chose to cut it myself, both the company I bought the stone from and the company I bought my saws from told me it would be impossible to cut it is thin as I wanted. While some varieties of stone are definitely easier to work with than others, I’ve been able to get very precise cuts using diamond blades.

Most of the stone used in this project starts as 12″ x 12″ stone floor tiles which I cut on a wet saw into into strips as thin as 1 mm. Sawing it all myself provides so much more control— by varying the widths as needed, I can follow the underlying form much better. I use a lapidary grinder to shape the stone in areas where tile nippers are not precise enough.

It was important to choose whether the mosaic would emulate human anatomy or emulate the specific drawings. I chose to emulate the drawings themselves, which has a big impact on choice of colors and style. Interpretation of the drawings is a big part of selecting the right stone— for instance, to achieve the crosshatching used in the drawing’s shading, I cut striated limestone from four different angles (with the grain, across the grain and both 45° angles to create a chevron effect). For the eyes, I am using red-brown star sapphire cabochons that protrude from the surface just enough suggest eyes. The circulatory system will be done in lapis lazuli and red jasper. It’s often somewhat difficult to tell from one drawing whether you’re looking at fascia, tendon or a bit of bone so I often cross reference with other anatomical drawings or better yet, photos of dissections.

Detail showing ruby eyes

Progress to date—

The first thirteen are complete and installed in their frames. That puts the project firmly at the halfway mark. I am currently at work on number fourteen.

Each mosaic takes about 600 hours to complete, not counting slicing the stone tiles into strips which was done in advance.

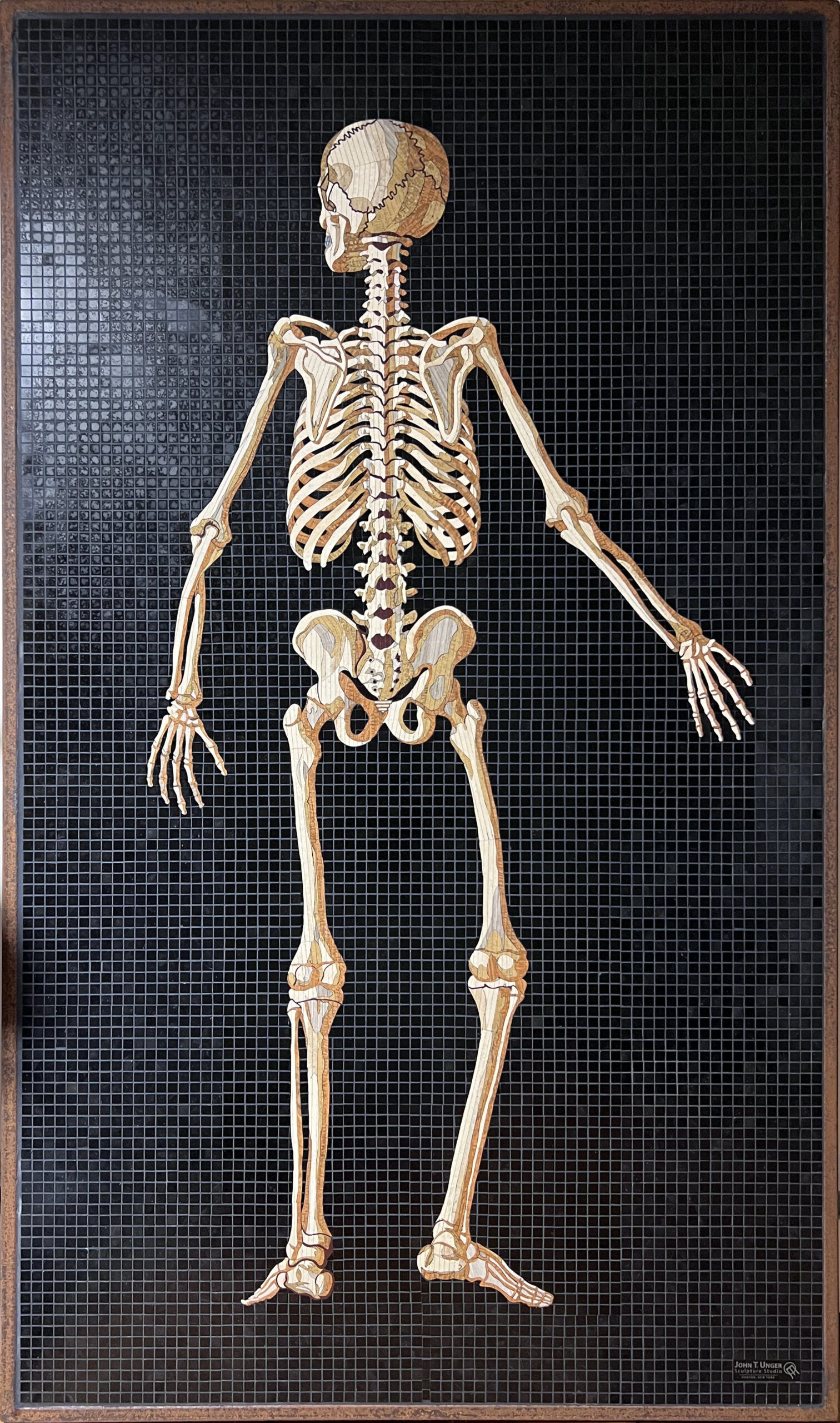

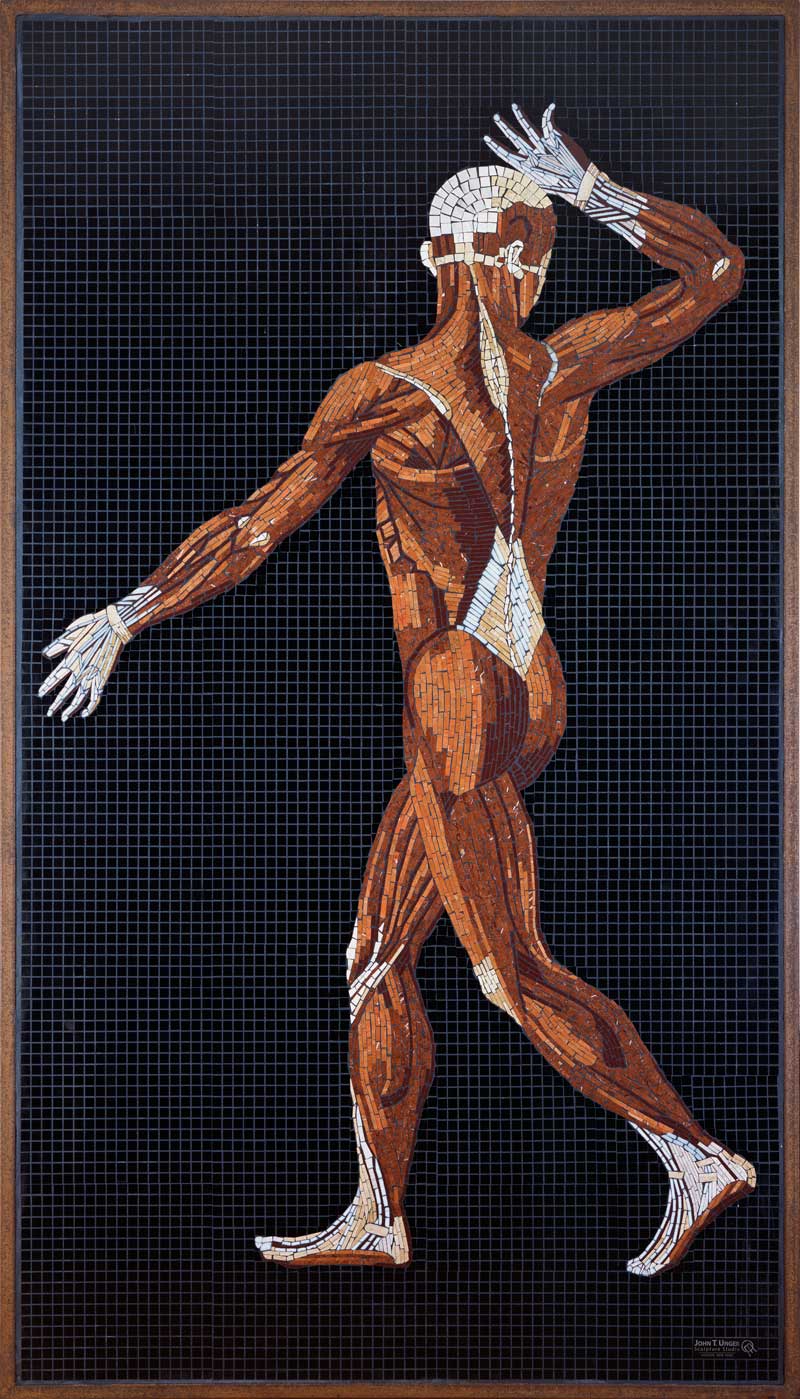

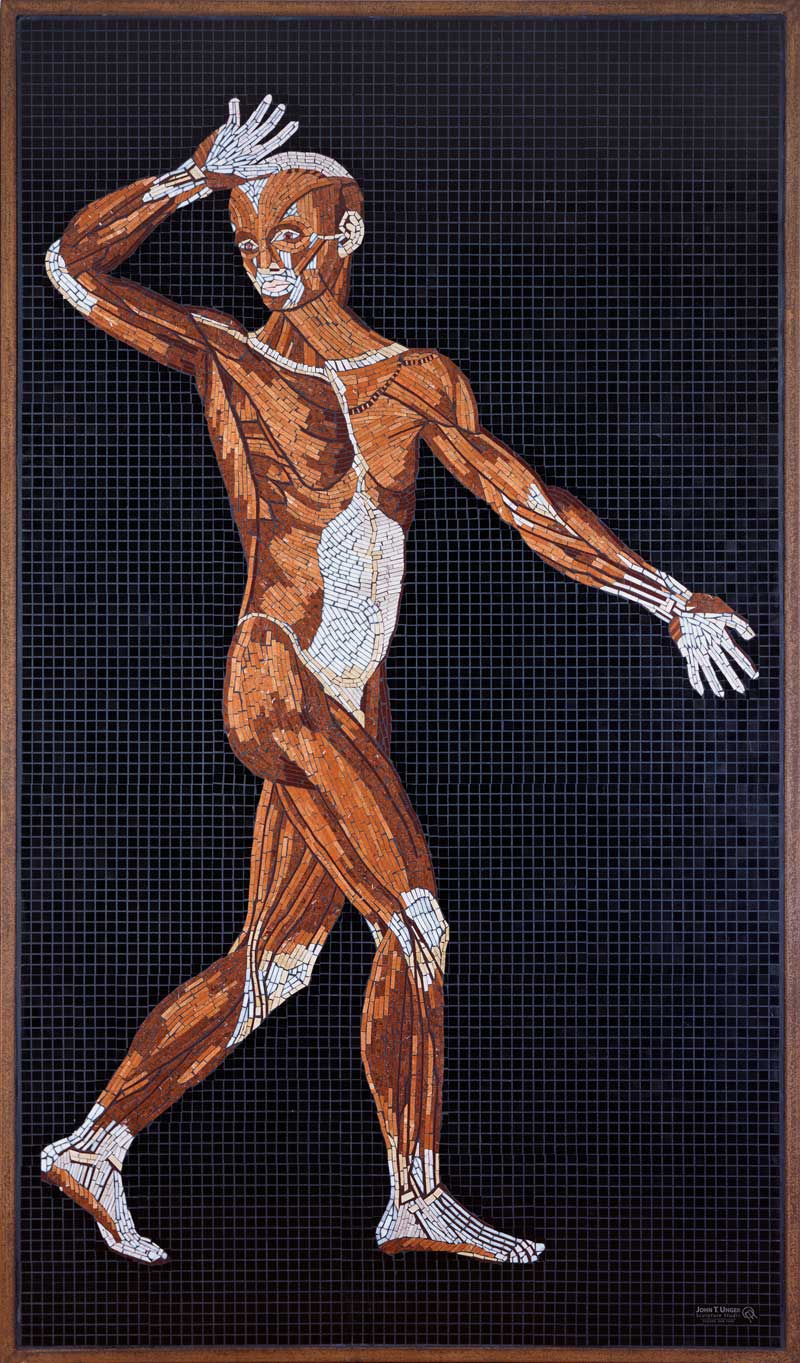

Marble Mosaic of Table 31 of Eustachi’s Tabulae anatomicae, 2017

Marble Mosaic of Table 30 of Eustachi’s Tabulae anatomicae, 2017.

Marble Mosaic of Table 28 of Eustachi’s Tabulae anatomicae, 2018.

Marble Mosaic of Table 23 of Eustachi’s Tabulae anatomicae, 2018.

Marble Mosaic of Table 21 of Eustachi’s Tabulae anatomicae, 2018.

Marble Mosaic of Table 38 of Eustachi’s Tabulae anatomicae, 2019.

Marble Mosaic of Table 33 of Eustachi’s Tabulae anatomicae, 2019.

Marble Mosaic of Table 19 of Eustachi’s Tabulae anatomicae, 2019.

Virtual Tour of the Exhibit Design

I used Artsteps to create a 3D virtual art gallery that models how the exhibit will look when complete. To navigate the virtual space, use your keyboard arrow keys (up, right, down and left) or use your mouse, by clicking where you want to go. You can make the VR gallery full screen by clicking the screen icon near the top of the right side.